Conditioning: More than running laps and ‘On the Line!’

By Dr. Joe Eisenmann

It is not the purpose of this article to provide a “recipe book” or a complete conditioning plan but instead to provide the coach with further information to assist in designing conditioning programs.

A review of energy systems

Energy production in the body occurs via three ways: immediate, short-term and long-term.

The immediate energy system relies on the available high-energy biomolecule called ATP within the muscle cell and its resynthesis via another super-charged biomolecule, creatine phosphate (CP). Because of this relationship between the two compounds, the immediate energy system is referred to as the ATP-CP or ATP-PC (phosphocreatine) system. The ATP-CP system is predominate during high-intensity, high-power output activities such as explosive jumping or sprinting lasting up to about six to 10 seconds.

In addition to harvesting anaerobic energy via the ATP-CP reaction, carbohydrate metabolism can also contribute to the energy demands of active muscle during short-term, high-intensity work bouts lasting between 15 to 90 seconds. Carbohydrate metabolism occurs in a series of chemical reactions called glycolysis and produces the by-product lactic acid. Thus, the short-term energy system has been called the anaerobic glycolytic or lactic acid system.

During prolonged sustained duration – more than three minutes – or low to moderate intensity exercise, the supply of oxygen via the cardiorespiratory system can meet the energy demands of working muscle by aerobic metabolism of carbohydrates and fats. The aerobic system is often referred to as the endurance system because of its function during prolonged duration activities.

Energetic demands of football

Although a high school game is comprised of four 12-minute quarters, it occurs in a series of repeated short but high intensity plays with a typical recovery time between plays of 20 to 40 seconds. It has been suggested that about 90 percent of the energy production during a football game is provided for by the ATP-CP energy system, while the most of the remaining energy production is the result of the glycolytic energy system.

However, we should not dismiss the role of the aerobic energy system in recovery or more up-tempo offensive play. This is merely suggested by experts based on sound rationale as there is no research which has investigated the physiological response of players during an actual football game.

The average time per play and rest between plays allow for a more precise understanding of the physiological demands of the game. It also provides important information related to the exercise prescription for conditioning.

More recently, the use of GPS technology has provided further insight into the movement characteristics and physical demands of the sport. Former University of Michigan and current New York Giants strength and conditioning coach Aaron Wellman and colleagues monitored 33 NCAA Division I players during 12 regular season games. They found significant differences between offensive and defensive positional groups, with receivers and defensive backs completing significantly greater total distance, high-intensity running, sprint distance and high intensity acceleration (positive and negative) efforts than other positions.

These total distances reached ranges of 3,013 to 5,530 meters, including 655 meters of high intensity running with the high intensity portion – about 5 to 20 percent – made up of approximately 10 sprints and 100 accelerations depending on position. This added information, beyond number of plays and time per play, etc., provides context to what happens during a course of a game and can further aid in the development of conditioning programs.

Conditioning for football

Here are a few examples that can be used when designing conditioning programs.

In the first example, athletes perform five sets of five repetitions covering 40 yards with a three-minute rest between each set. Each rep consists of either a jog, run or sprint for a specified distance over the 40 yards. The recovery between reps also varies between 15 to 30 seconds.

For example, the first rep consists of a 10-yard jog transitioning to a 15-yard run and then into a 15-yard sprint. The athlete is allowed a 15 second rest and then commences the second rep returning the other way. This rep consists of a 5-yard jog, 15-yard run and 20-yard sprint. There is then a 20 second rest prior to the third repetition.

The sets, repetitions, distance and recovery can be altered depending on the goal of the training session.

Another consideration is to incorporate other movements, transitions and change of directions into the drill. As an example, follow a dynamic warm-up with a short session of techniques of acceleration, deceleration and change of direction in which athletes move through a series of movements that cover all directions – forward, lateral, backpedal, deceleration right foot, deceleration right foot and transitional change of direction movements such as forward to backpedal, shuffle to sprint and all combinations.

This ensures that athletes are being trained in all planes of movement and all general movement patterns instead of the specific movement patterns dictated by their position. Of course, this occurs in isolation but the point is that we are not conditioning for the sake of conditioning but focusing on movement quality and technique, and injury prevention.

To contrast, let’s think about an image of a coach with the whistle yelling “on the line”. Conditioning does not need to and should not be conducted in complete isolation. Conditioning should be incorporated into practices. This gets to the idea of economical training.

The relative importance of conditioning for sport also must be put into perspective with the importance of meeting the other needs – cognitive, psychological, tactical, technical – of preparing athletes. Given the limited amount of practice time, coaches should plan activities which simultaneously meet the needs of more than one area.

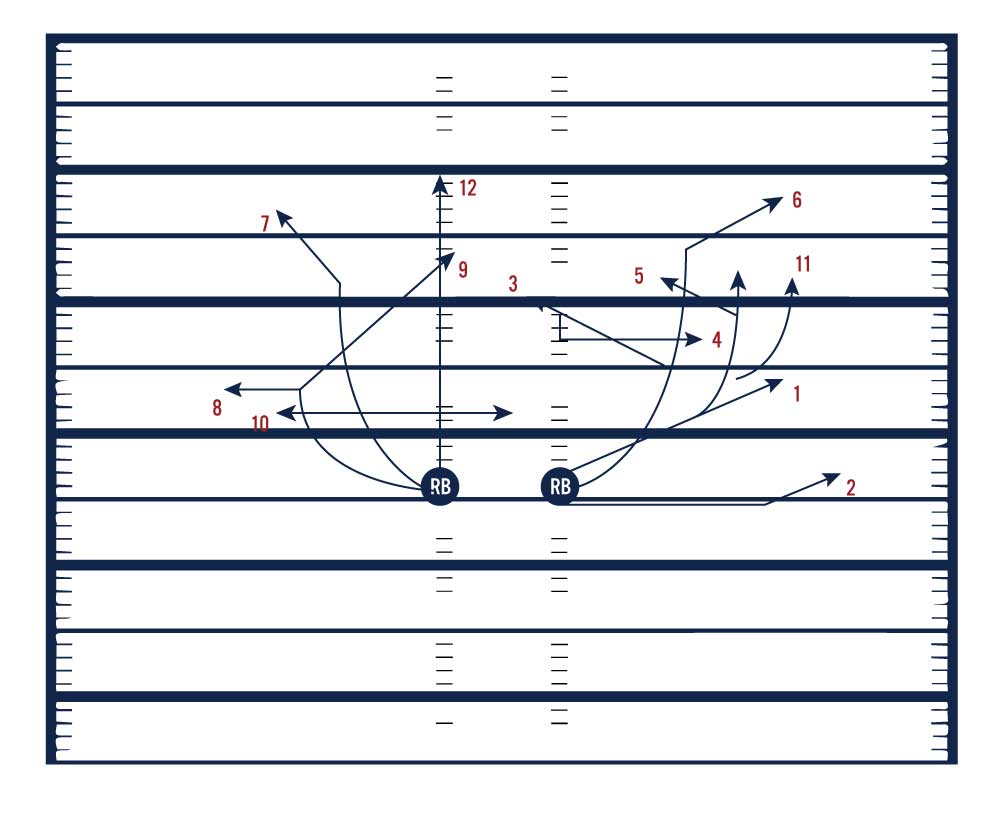

An example of economical training is shown here.

This could be part of an individual period when athletes are placed into position groups. In this example, offensive position groups are shown. Similar to the example above discussing development of speed and agility technique, the position coach should be coaching skill technique during this period, but we are executing at an up-tempo pace similar to what will be observed during a game.

The QBs can be executing drops and rollouts and throwing to receivers. The running backs can be working on ball security and cutting and accelerating. This is also a great time to allow RBs to get creative and explore moves. Receivers are running routes, and the offensive linemen are working run and pass block technique and releasing downfield to get to line of scrimmage.

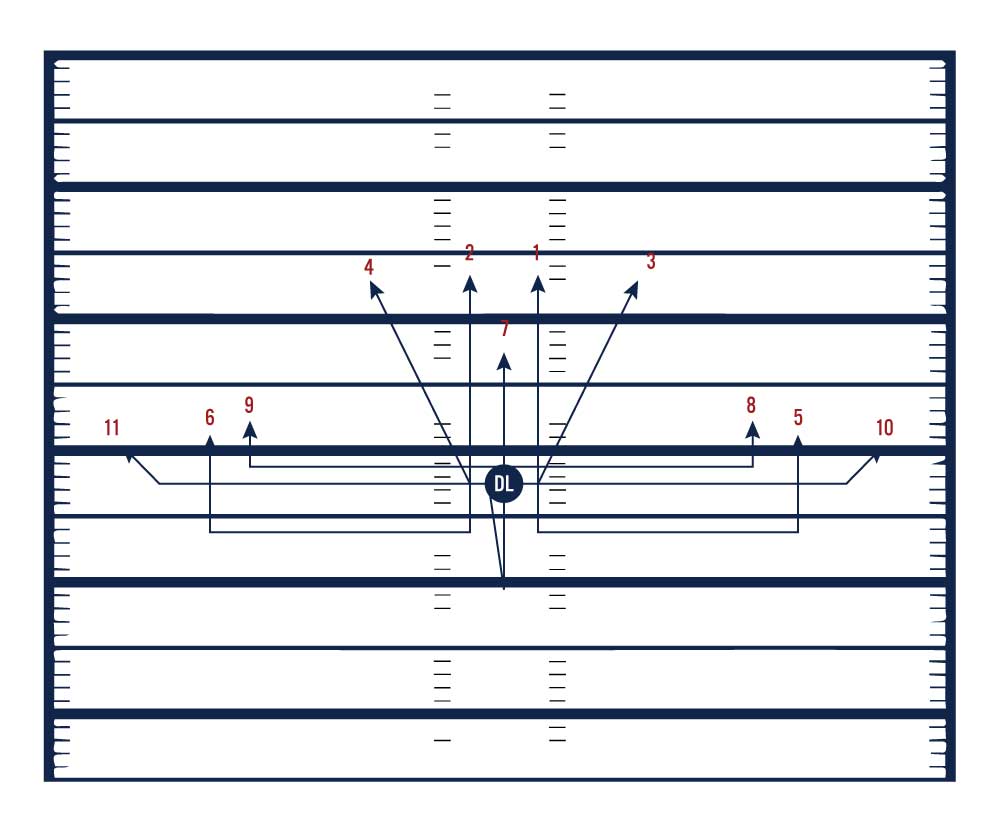

Football requires cognition and decision making under pressure and in a fatigued state. An approach used by USA Football’s Keith Grabowski involves a live on-field drill with coaches serving as the signalers and spotter.

After receiving the play, the offense runs the play on air. This can be done as described but Grabowski has incorporated it with an interactive playbook where the players utilize their smart phones and videos created within the system.

Here’s how it works: The player opens the app on his phone (in a wristband), and the starting yard line and hash is given via text on the screen. This gives the player a cue about his alignment on the field. The player gets aligned as fast as possible and executes a six-second burst that includes whatever their assignment is by position. For example, a guard might pull for an imaginary linebacker, or a receiver might run a post route. Regardless of the player, a six-second high intensity effort with execution of the assignment against an imaginary defense is expected. Each play finishes with a question about the assignment via the video quiz and the player is given a coaching point related to their response. The series continues as the player receives his next alignment, hash and field position through the video. The process repeats until the drive is completed. For a detailed account of this process see the following link:

It is important to consider that football is played in a dynamic and chaotic environment. Thus, conditioning sessions should reflect the changing frequency, intensity, duration, distance and recovery time between bouts.

Use the average and range of duration of play, yard per play, recovery time between plays, plays per series and time between series to get your players ready for game day.

Dr. Joe Eisenmann is the director of high performance and education at USA Football. Prior to this position, he was a professor of pediatric exercise medicine at the University of Wyoming, York University, Iowa State University and Michigan State University. In 2012, he founded Spartan Performance, an integrated sports performance center at Michigan State University that tests, trains and energizes 2,500 youth athletes and more than 200 coaches on a daily basis. His interests cover the areas of long-term athlete development, testing and assessment, sports science and analytics, athletic health, youth fitness, and coach education